The "Mr. Big" undercover sting that convinced two B.C. teenagers to confess to murdering a Seattle-area family is unreliable and can lead to false admissions, according to a criminologist who's studied the scheme.

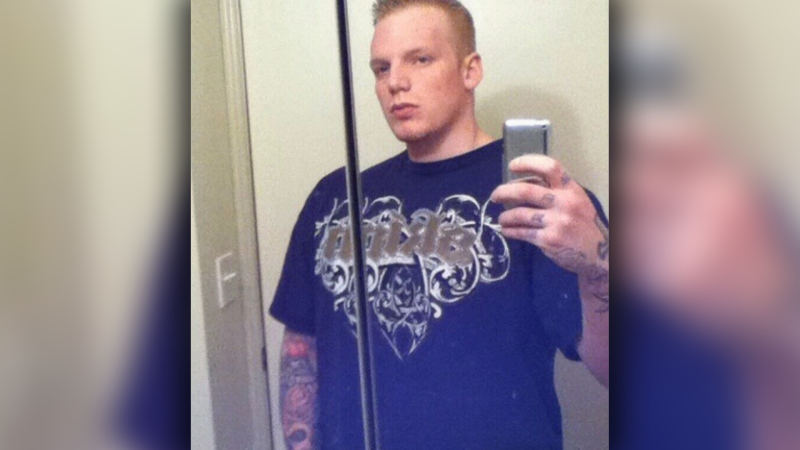

Sebastian Burns and Atif Rafay were sentenced to life in prison with no parole for beating Rafay's parents and autistic sister to death with a baseball bat in 1994. The West Vancouverites were each just 18 years old at the time.

The two men began appealing their convictions in a Seattle courtroom Friday, arguing that their confessions were false, and that they were frightened into admitting the crimes to people they believed to be dangerous gangsters.

The RCMP's so-called "Mr. Big" scheme has been used across Canada to find evidence and elicit confessions from suspects in serious crimes.

But according to Kouri Keenan, an SFU criminologist who studied 81 cases in which the scheme was used, those confessions are often unreliable and sometimes even false.

"We found that there were issues related to the reliability of assertions made by targets, because the police are able to circumvent many of the procedures and evidentiary guidelines that govern how they conduct their investigations," he told ctvbc.ca.

Posing as powerful crime bosses, undercover cops offer suspects a chance to join their underground organizations if they can prove their worth. Investigators have been known to fly targets across the country first-class, take them to strip clubs, pay them for small jobs and offer them tens of thousands of dollars.

"The things that they might not able to do, they are able to do because the suspect believes them to be a criminal cohort," Keenan said.

"They encourage boastfulness and bravado. [The suspects] might confess to achieve notoriety. They might also confess to secure significant financial inducement."

In the case of Rafay and Burns, the two men say that they were scared that they might be hurt if they didn't confess to the murders.

Their confessions were caught on video, however, and prosecutors pointed out that the men appeared calm as they described the vicious slayings, sometimes even laughing.

But Keenan says that doesn't necessarily mean their confessions were valid.

"That's often seen in these interrogation tapes, and what the suspects always claim in hindsight is that they were frightened and they didn't want to piss Mr. Big off, and they were just telling him what he wanted to hear," he said.

The RCMP is not commenting on the technique, citing the ongoing court proceedings in Seattle. Court proceedings in the appeal are being broadcast live online.

Pressure to confess can be ‘overwhelming'

The Mr. Big technique has been endorsed by the Supreme Court of Canada, but it's not permitted in the U.S. It's particularly popular in B.C., where Keenan says he found 56 of the 81 cases he studied for his book "Mr. Big: Exposing Undercover Investigations in Canada."

Canadians judges have thrown out evidence from Mr. Big stings in the past, though.

Clayton George Mentuck was charged with murdering a 14-year-old Manitoba girl in 1996. He confessed the killing to a police operative posing as a gangster, but Judge Alan MacInnes rejected that evidence because of the "overwhelming" pressure to confess.

"There was nothing but upside for him to admit and nothing but downside for him to deny the offence. If he were to admit to the killing, he would thereby demonstrate his honesty, loyalty and integrity to the organization, having been told repeatedly that the organization knew he had done it, did not care that he had done it, and had someone who would admit to the offence," MacInnes wrote in 2000.

"To maintain his denial would mean that the stigma of this offence would continue to hang over his head, that the police would continue to bother him about it in the future, that he would not receive the [promised] $85,000 and indeed would be out of the criminal organization and the job and income which that provided."

In 2009, Kyle Unger was acquitted of murder after spending 13 years in prison. He had confessed the crime to an undercover officer, but DNA evidence later proved him innocent.