The B.C. man who was acquitted Wednesday for a string of rape charges in the early 1980s said he's not angry about spending nearly 27 years in prison for crimes he didn't commit.

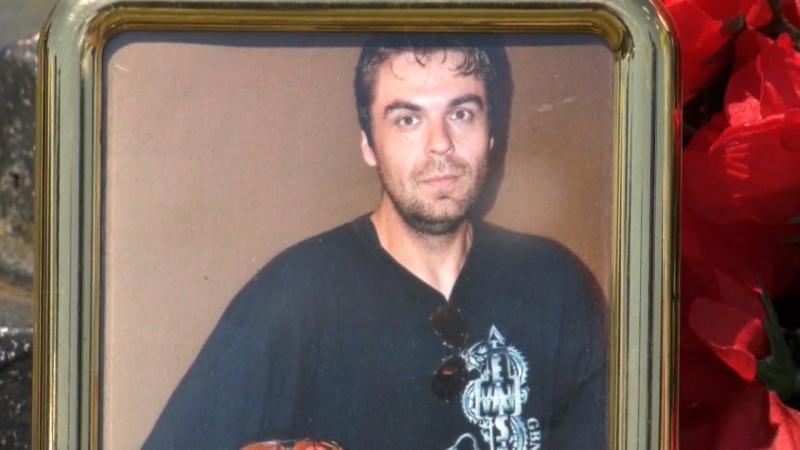

"It wouldn't heal me if I was angry," Ivan Henry, now 63, told reporters outside of the B.C. Court of Appeal, flanked by his two adult daughters.

"I got grandkids that I'm so proud of and I got a little dog that I look after and he's my friend. It's just the way it is."

Henry also had a message for people who are incarcerated and trying to fight their wrongful convictions.

"Don't give up. Keep plugging ahead and work to get out and to learn what society's all about. It's not all a dirty world. We're all here to try and help each other."'

The appeal court justices were unanimous in quashing Henry's 10 convictions. Henry was the victim of a number of legal errors, a botched police investigation relying too heavily on eyewitness evidence, and his own lack of legal counsel, according to Justice Richard Low in his judgment.

"Each complainant was subjected to a terrifying experience at the hands of a dangerous man. However, the evidence of eyewitness identification was not capable of establishing to the standard required by law that the appellant was that man."

Low said that it was a mistake for police to hold Henry down in a lineup photo while others smiled for the camera – and another mistake for prosecutors to use Henry's struggles as an admission of guilt.

"This error would also irretrievably taint the verdicts," he said. "I would allow the appeal, quash the convictions and enter an acquittal on each count."

Relief

The ruling ends nearly three decades of turmoil for the Henry family, who lives in North Vancouver.

Adult daughters Kari Henry and Tanya Olivares, who were put into foster care after their father's incarceration, have steadfastly believed in his innocence.

"I'm just amazed," Kari Henry told reporters outside court. "I'm so happy, really, really happy. This is a huge weight off our shoulders."

Olivares said their family is ready to move on with their lives.

"Justice prevailed today and we're just going to move ahead," she said. "This has been a sentence for my dad but it's been a sentence for me and my sister -- my children. We just want to live a normal life."

She said her father returning home has been a huge adjustment for everyone in the family.

"He came home 16 months ago to a family who he didn't really know, and we didn't know him. He had to come into a busy family life. He has adjusted like nobody else could have. He is truly amazing. I am so proud of him."

Henry said leaving prison after so many years was difficult, and he was bothered by large crowds of people.

"It was really hard on me because I come from 1982 we didn't have the same amount of people … the world changed big-time."

The case

The saga began with a string of more than 20 sexual assaults over just 18 months in the early 1980s. In each assault, the perpetrator told his victims that they or someone who lived in the same house had "ripped him off" as a pretense to gain entry to the suites.

The Vancouver police investigators concluded the assaults were by the same man, and in the midst of a lot of public pressure to solve the case, arrested Henry in 100 Mile House in 1982.

Henry had to be held down by officers as he struggled in a police lineup photo. The victims were then shown the photo, and many identified him. Henry was the only person held down by police.

It's clear that Henry himself had a sense of the miscarriage of justice, for he argued on the stand that the photo shouldn't have been included.

"A lineup of that nature wouldn't have to be put to the jury because it would be – it would be against the law, because the jury couldn't decide if the guy is guilty or not guilty," he said during his testimony in 1983.

"I never refused anything to anybody," he said in his cross-examination. "All I said is…it's not a fair lineup."

He was convicted in 1983.

After his conviction Henry appealed in person in 1984, but the appeal was dismissed on procedural grounds. The Supreme Court refused to hear the case that year. Henry followed up with a string of other applications, but all were dismissed.

Thirteen years after that, Henry tried again -- but was told no court had jurisdiction to hear his case.

It was only during a police investigation of unsolved sexual assaults prompted by the Pickton investigation that the case was reopened. "Project Smallman" used DNA evidence to find a man only known as "D.M." , who pleaded guilty to three offenses and was sentenced to five years in prison.

But the similarities to Henry's case prompted prosecutors to appoint Leonard Doust to investigate a potential miscarriage of justice. On January 13, 2009, the court ordered Henry's appeal reopened because of "exceptional circumstances."

With a report from CTV British Columbia's Jon Woodward