Forget the princesses -- it might be time for Mario and friends to start searching for the missing software revenue.

In October, Nintendo, which has enjoyed massive success since the release of its family-friendly Wii console, announced a 52 per cent drop from March to September 2009.

And that's just the tip of the iceberg. North American game and console sales have been dropping industry-wide for seven consecutive months, and developer layoffs have plagued the gaming business since the recession hit in fall 2008.

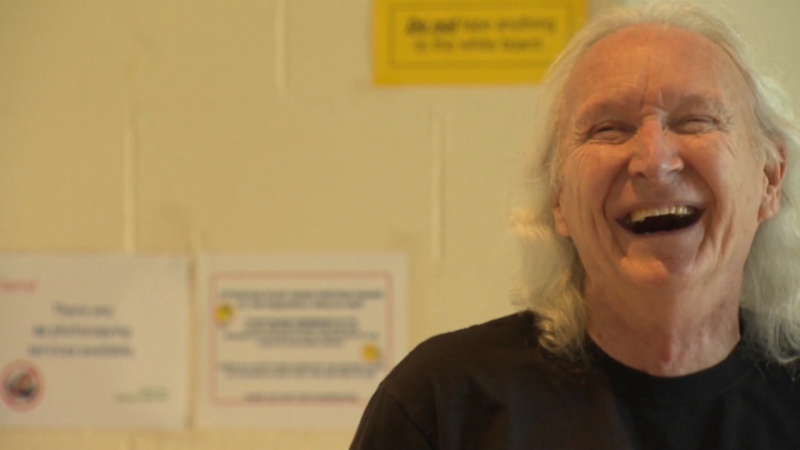

But industry vet Anthony Gurr says the economy is only partially to blame.

"The amount of financial failure in videogame development is generally huge," Gurr said. "Several thousand titles come out every year. Four-fifths of those are just not going to make a profit."

With that in mind, many software developers have looked to a former niche market that has emerged as a major player in game sales. Namely, cell phones.

Producing a video game for a major console is akin to filming a Hollywood blockbuster, Gurr said, and with costs approaching $100-million.

As a result, AAA titles generally sell for $59 to $69 each.

But developing online games and portable phone applications is comparatively cheap, and can be done in small teams or even by individuals. Games can then be sold for less than $5 or $10 -- while still turning a fair profit.

"[Online puzzle game] Bejeweled took something like six months to make and cost about $60,000," Gurr said. "They've made millions of dollars back."

Earlier this year, Nintendo representatives went so far as to explicitly blame Apple's massive iPhone and iPod Touch presence for its own dwindling sales.

So has the iPhone marked the end of console gaming, as consumers have traditionally known it?

Gurr says no -- at least not entirely.

"Seventeen per cent of people who play games are die-hard gamers," he said. "That number has been fairly consistent. There is still an audience who want to have the high production values and detailed back-stories you get on consoles."

And whether that will provide consolation to developers, who have already seen thousands of jobs axed over the past year, may be another story.

Gurr, an SFU master's student in education technology, has been involved with the industry since the '80s, when he joined the production of 8-bit NES classic Bubble Bobble.

His first academic paper, "Video games and the challenge of engaging the next generation," will be published in a textbook on educational gaming next month.